For the past two years or so, designer Eli Schiff has been causing a stir among his fellow product designers with the critical essays he’s been publishing on his web site. With titles like “Instagram’s Abomination,” “Uber’s Atomic Meltdown,” and “Fall of the Designer,” these writings have taken the design industry to task for recent trends in product design, branding and aesthetics. In particular, Schiff spends significant energy examining what he believes is a harmful tendency among designers towards undervaluing their own contributions.

Schiff’s essays have been polarizing, to say the least; while they have had their share of defenders, many within the design community have condemned them for both their substance and style. For me, as a proponent of more thoughtful criticism within our trade, I’ve been reading Schiff’s writing with great interest. The often impassioned backlash to his writing has been eye-opening; for good or bad, it has shown that close scrutiny of how design functions at the intersection of business and technology inspires strong feelings. In my view, Schiff’s work clearly raises some worthwhile if provocative questions, though the language of his arguments often seem less than ideally productive.

After reading many of his articles, I became very curious about his motivations and the way he perceives the impact of his work, so I suggested an interview. Over the course of several months, sometimes with long pauses due to scheduling on both sides, we conducted this interview. If you’ve already formed an opinion about the value of Schiff’s work, it may not alter it, but at the very least it will help you understand a little bit more of what goes into those controversial essays.

Khoi Vinh: I think a lot of people know your writing but not as much about your background. Can you start with a brief overview?

Eli Schiff: Growing up in Massachusetts, I gravitated towards the arts, but it was more a hobby than anything. After high school I took a gap year to teach a third grade class, and then went on to pursue a business degree at UMass Amherst.

About halfway through my studies, I started to explore Photoshop in my free time and quickly shifted focus towards design. My school didn’t have a design program, but a couple faculty members supported my building an independent curriculum. Among other things, I did design writing, worked freelance and reached out to the small Boston design community.

Since then, I’ve worked in-house and consulted with a variety of companies, while at the same time deepening my critical writing practice.

How did you begin your critical writing about design?

As a teen, I loved to read books by writers like Thomas Paine, Ambrose Bierce and Christopher Hitchens. The subject matter they dealt with was captivating, but it was their biting style and commitment to criticality that resonated most.

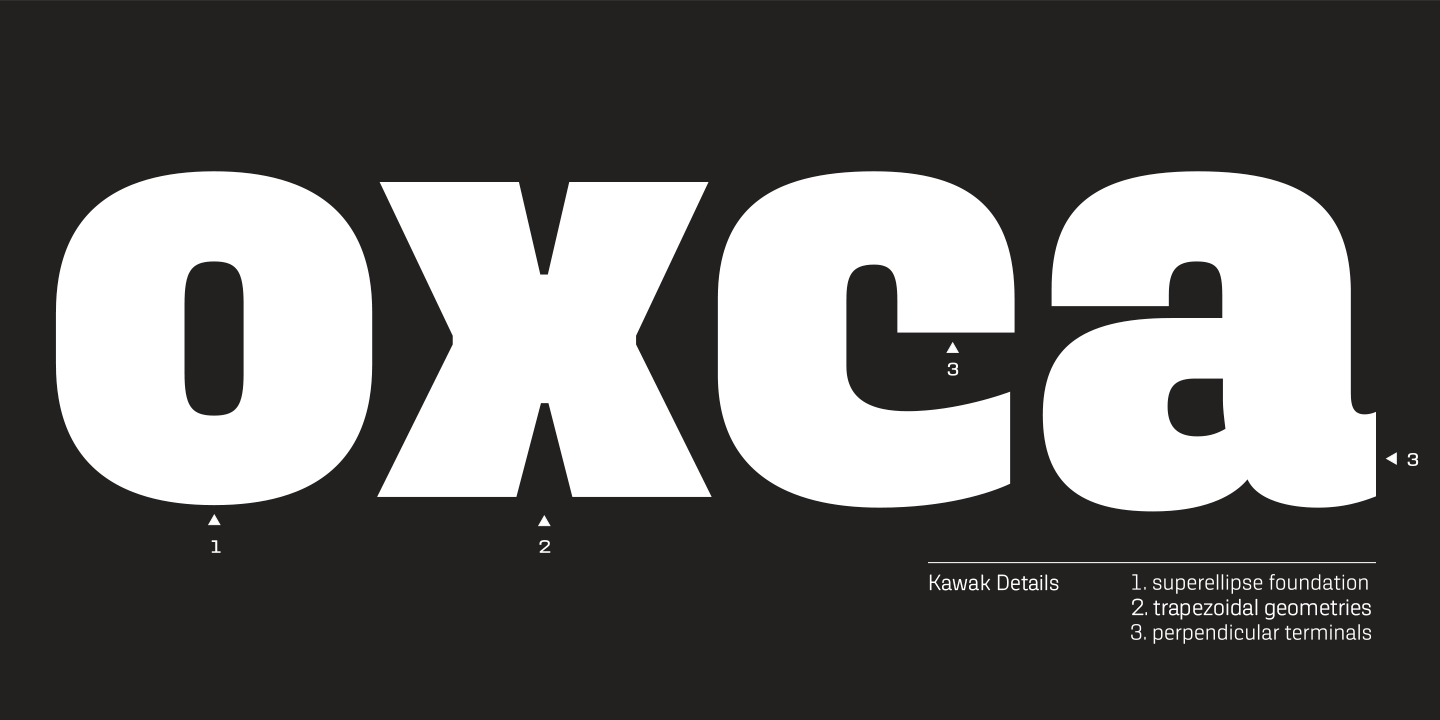

Also, in my early days in the icon and UI customization community (MacThemes, DeviantArt and Dribbble), I was lucky to be involved in a small cohort of mutually critical designers. I found myself coming to write implicitly critical commentary about broader history and trends, and over time that gradually turned into the longer form criticism I engage in today.

You say “gradually”—does that mean it was mostly a subconscious progression? Or did you decide early on to explicitly write criticism about design?

As far as my associating with the term ‘criticism,’ it was definitely subconscious to begin with. I only explicitly adopted the title after I had built up a body of critical writing on design. At that point, it clicked.

At this point I think some people would say, “Is he qualified to be a design critic?” How would you answer that?

If the interlocutor were a designer, I would ask them ‘what qualifies a designer to design?’ The two professions are here analogous. In the same way a designer is hired by clients to design, a critic is hired by their readership to write.

Most of us can remember exiting a movie theater in a heated discussion with friends about the quality of the acting or special effects. In this way, every one of us engages in criticism, though it’s usually informal.

Having said that, few have the patience to research history and theory, let alone a desire to publish their perspectives. What differentiates me as a professional critic is being compelled to maintain a critical practice as a living.

So do you see yourself as different from any other designer writing about the craft on his or her blog or on Medium, say?

The danger of a platform like Medium is it encourages a sort of drive-by approach to writing. Of course reaction pieces are essential. But as far as my critical practice goes, I find a lot of value in being able to source years’-worth of extended research living in notes, graphics, mind-maps, outlines and half-written essays.

What I’m trying to get at is whether you regard your critical writing as something different from the common design discourse we find on the Internet circa 2016. Your thoughts on that?

So much of design writing is promotional, beholden to a particular company’s design ideology. Diverging from that, there are a handful of cultural critics who write about the aesthetics of politics, of broader societal issues. But I am one of the few critics who distinctly tackles the politics of aesthetics itself, of style and beauty.

Let me see if I can summarize your central focus. It’s the idea that style and beauty are more than just superficial aspects laid on top of functionality, that they deserve thoughtful consideration of their own, and that designers are too readily dismissive of them in the pursuit of legitimacy in business. Does that sound right?

Well put! It’s a big part of what motivates my writing.

Can you give some examples of where you see this play out in the industry?

Right now I’m focused on articulating where this anti-aestheticism emerges from and how it plays out in visual design and software. Those who take the time to read my criticism can begin to understand why.

For the sake of readers of this interview, can I get you to cite some examples?

Recently I took to Twitter to publish some informal criticism of the new logo for a well-loved brand. Most in the design community were supportive of the refresh, as the brand got a new logo, site and products, accompanied by a lengthy case study. I didn’t intend for the critique to be contentious, but it spread like wildfire, quickly getting around a million impressions.

My critique centered on the observation that the new logo suffered a loss in character—though that’s par for the course. What surprised me was that my numerous detractors didn’t leap to the designer’s defense and justify any qualities of the logo as you might expect. Instead, they exclaimed that the logo simply did not matter.

Why did they argue the logo didn’t matter? Two reasons: first, they felt the products the logo would be emblazoned on were sufficiently appealing. But even more callously, some apologists argued that the logo didn’t matter because the brand would inevitably remain profitable. Of course neither retort addresses the criticism I levied. Quite the opposite–they simply backhandedly insulted the designer they sought to defend. It is this sort of anti-aestheticism that drives much of our discourse.

Do you think “anti-aestheticism” is something endemic to the craft, or do you think it’s been driven by particular circumstances? What would you say its origin is?

Absolutely. Modernist functionalism is all but indistinguishable from design itself. They have been tied together since the inception of the craft.

None of this is all that surprising if you look at the political benefits of modernist ideology. Consider that design must appeal to business for its very survival. The edifice of modernism offers a false sense of stability in a sea of uncertainty.

What do you mean by that last remark? What’s that “false sense of stability” you’re referring to?

How else could I describe an ideology that believes it has always and will continue to achieve objective and universal form? It is pure hubris set in a monochromatic palette.

I would doubt that most designers who aspire to a modernist, minimalist or “flat” aesthetic really believe it leads to a truly objective or universal form. Many of them, if not most, probably believe that it’s a way of working that benefits the end user. Would you agree?

I agree most people believe they’re designing in the interest of the end user. Whether things work out that way is another story.

That said, I’d emphasize that many influential designers indeed do believe modern minimalism results in objective and universal form. Those designers without said belief either aren’t reading the canon, or aren’t internalizing it.

So do you contend that even if a designer doesn’t believe in Modernism’s foundational values (“objective and universal form”), working in the Modernist framework is nevertheless a mistake? Even if the designer has a different interpretation of what it represents and what it means?

Let’s take for instance the grid. You’ve been a major proponent of designers understanding grids, even if the intention is to subvert them. Designers who entirely ignore the topic of grids miss out on something deeply important in their education.

What I’m getting at is that in using certain tools, designers run the risk of reifying the ideologies that are associated with them. This is most true when tools and techniques are fetishized, which is the tendency among designers. So the designer who works within the frame of modernism is, in the artifacts he’s producing, not untouched by it.

I would agree with that. But are any of these tools—grids, Modernism, skeuomorphism, whatever—inherently good or bad? My feeling with Modernism in particular is that it’s so pervasive, especially if you account for its many permutations, that to judge it all as bad seems counterproductive. Similarly, there’s an argument that capitalism is bad, but that doesn’t really get us anywhere.

Are the tools themselves inherently bad? No—but neither are they inherently neutral.

As you point out, capitalism and modernism are vast enterprises, but they are equally worthy of inquiry as both broad categories and in their specifics.

We’re getting into the finer points of this argument, but I wonder if you believe it’s been effectively communicated to—or heard by—your audience?

That’s why I’m happy to say there’s much more to come on my blog.

I’ll be more direct: there’s a sense that generally your critiques are focused on negativity and pejorative evaluations and less on substance. I think it’s probably fair to say that there’s a bit of inflammatory language in your writing. Is this, for you, an effective mode for communicating your ideas?

I’m very deliberate about writing. It’s true, some people don’t have the stomach for my style. On the other hand, my writing was never intended to be for everyone.

Also, I question the premise that negative critical appraisals are antithetical to substance. If anything, writing a critical pan should inspire one to grapple with their subject.

Maybe it’s the hyperbole that riles many people. A few examples: you called Instagram’s recent rebranding an “abomination.” You said that modern minimalism tends toward “intentional obscurantism” and is aimed towards elevating “a class of would-be elite designers and their sycophants.” And you dreamed up an “Unofficial Apple Icon Awards” which, though satirical, many found to be mean spirited. There’s a an undercurrent of dismissiveness and heightened negativity in these writings. Some would say they stray beyond critique and into maliciousness. How would you respond?

Be glad I use the language I do. It’s rare to find this sort of honest polemic elsewhere given the incestuousness of the design community.

Final topic: what do you think it would take to have more robust critical writing and thinking about product and interaction design? And what do you think needs to happen to even convince designers that that’s necessary?

On one hand, designers already embrace criticism. As I mentioned earlier, we all take to social media to appraise the latest logo redesign. At the same time, most people have a strong aversion to making something more of these everyday acts of criticism, as that invites a scrutiny of its own. As far as I can see, the way forward is to lead by example.

+